Cycle of Life in Traditional African Art

One of the most pervasive concerns in African societies is continuity of life. Much emphasis is put on the fertility of man in African contemplation and art. The concepts of prayers to God, the pleading with Idols and the Ancestors rituals, are all meant for one reason, to strengthen and ensure life: “Give me life, give me power and strength and make the family bigger”, As a need to ensure the continuity of descent and prevent the cutting of the family line and the cycle of life.

The future of family and society depends on the current generation’s ability to procreate and bear children. The sense of social and biological completeness of the individual is achieved only by his or her ability to be a parent. Children not only guarantee the well-being of the individual while alive, but also in death – they will provide a proper burial and ensure the transition of the spirit of the parent to the afterworld, to take its place as an ancestor and reincarnated as a future family member.

One of the strongest beliefs of the Africans is reincarnation. The word reincarnate means “a constant cycle of life”. According to African understanding, the soul returns in every cycle. When a man’s life ends, a new one begins, and thus the eternal cycle of parents and relatives continues. Barrenness, therefore, is considered a terrible curse, as it stops the cycle of rebirth: "A person who has no descendants in effect quenches the fire of life, and becomes forever dead since his line of physical continuation is blocked and cuts down the family line".

To ensure a healthy pregnancy and birth, the Africans employ spiritual aids and most Mother and Child figures are meant for that. The main role of the African woman is to become pregnant, give birth and raise the children. When a couple can not bear a child, or their child dies, the woman is considered responsible. A childless woman bears a scar which nothing can erase. She, her family and relatives will suffer for that – an irreparable humiliation with no source of comfort in traditional life.

In such cultural background one can find a multitude of Mother and Child figures in Africa. The mother and Child figures represent a state of natural purity - during the long breastfeeding period the woman is celibate. Therefore, Mother and Child statues represent more than just fertility symbols, they represent celibacy, internal purity, ceremonial purity, female empowerment and spirituality.

A dead man can be reborn, the protective spirit of the ancestor can reincarnate into a newborn child of his descendants or of another clan member. As soon as a baby is born they ask who sent this baby? who does he look like? Every new birth is rooted in the past, the soul and protective spirit are ancient. Sometimes there is no need to consult a Diviner as the similarity is so prominent, the identity of a specific ancestor is declared, and he is cast as the baby’s protective spirit whom gets his name. During the giving of the name they say “today Grandfather has returned home”. This is a never ending cycle of rebirth of the ancestor in the child.

With a cultural background such as this, one can find a multitude of images of mother and child and statues of ancient ancestors. These statues are the center of the current exhibition.

(Geoffrey Parrinder,The Psychology of Western Africa 1951; Roy Sieber & Roslyn Adele Walker, African art in the cycle of life 1987: 21-23; Herbert M. Cole, Icons 1989: 74-91).

Mother–and-Child and Fertility figures

Akua'ba Fertility Figure in Akan Art, Ghana

The focus here on Asante, Fante and Brong (Bono) people

THE MYTH OF AKUA'BA FERTILITY FIGURE

Akua'ba figure story is among the most famous legends in African cultural history. In central Ghana, a young Asante's woman named Akua (Wednesday born) was having trouble conceiving a child (ba). She consulted a local priest, who divined that Akua should commission a woodcarving of a little child. After it was blessed by the fertility deity in the rites conducted by him, Akua was constructed to treat the carving as if it were a living child: to carry it on her back, feed, Bath, sleep with it, and adorning it with beads, earrings and necklaces. When Akua appeared in the village with the carving on her back she was the target of mockery: "Look at Akua'ba" (Look at Akua's child). But eventually Akua became pregnant and gave birth to a beautiful, healthy girl. Her success encouraged other women struggling with infertility to follow her, and subsequently the carving was called Akua'ba in her honor (plr. Akua'maa or akua'mma). (Cameron 1996:43).

The legend and tradition continued as most carvers carved these “Akua’ba” dolls and people bought it with the belief that it will free them from a barren situation. Once the woman conceived and had a successful delivery, she would return the figure to the shrine as a form of offering. But if the child died, the “Akua’ba” might be kept by the woman as a memorial.

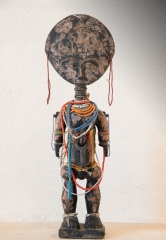

AKUA'BA Fertility Figure - ASANTE People

Disk-headed akua'ba figures remain one of the most recognizable forms in African art. Akua'ba were consecrated by priests and carried by women who hope to conceive a child. The flat, dislike head is a strongly exaggerated convention of the Akan ideal of beauty: a high, oval forehead slightly flattened in actual practice by gentle modeling of an infant's soft cranial bones. The flattened shape of the sculpture also serves as practical purpose, since women carry the figures against their backs tucked into the wrapper, the manner infants are carried. The fertility doll helps the aspiring hopeful young Asante women who firmly believe that the fertility figures will allow them to become pregnant. And this belief has stimulated the proliferation of the genre and the variations within it (E. Cameron 1996:56). Females are, with rare exceptions the only sex represented in akua'maa. There are several reasons, but the essential one is that the Asante society is matrilineal and family line passed from mother to daughters, not from father to sons (McLeod 1981a : 19, 164). Besides, daughters help in household chores and younger siblings (Sieber & Walker 1987: 44).

Akua'ba Fertility Figure - Akan - Fante

Although best known, the Asante Akua'ba is only one version of the fertility doll found among the various Akan peoples. The Fante and Brong (Bono) people who live respectively to the south and the north of the Asante’s also employ akua’ba dolls, for the same purpose as those of the Asante’s, however, the types are differentiated based on the style. While the heads of the Asante’s are round, flat and disk-like, those of the Fante dolls display long rectangular head and only rarely have arms, most Asante's figures are painted black, Fante figures are left unpainted. But Asante's and Fante's akua'ba dolls shared mutual face traits: eyes shaped like coffee beans framed by long, arching eyebrows that connect at the bridge of the nose. The mouth is generally positioned at the very bottom, leaving no chin. However, the Fante and Brong Akua'ba figures do the same functions and are believed as the Asante fertility dolls and shared the common legendary story of the doll's origination. The legend and tradition continued as most carvers carved these Akua’ba dolls and people bought it with the belief that it will free them from a barren situation (Cameron 1996:47-49).

Akua'ba Fertility Figure - Akan - Brong

The Brong living to the west of the Asante carved Akua'ba figure differently. The figure has typical head. Unlike the Asante disc-like, the Brong has a cylindrical head cut diagonally from the top back to the bottom front, producing a triangle in profile (E. Cameron 1996: 48-9). They were fertility dolls believed to assist barren women, to induce pregnancy or to ensure a safe delivery, and to have a beautiful healthy infant.

Ndebele Art

The Ndebele are well known for their outstanding craftsmanship, their decorative homes, and their distinctive and highly colorful mode of dress and ornamentation. They were once part of the Nguni-speaking peoples who settled along southern Africa's eastern coastal plain, but migrated to the central inland plateau. In the late 19 century, after the Ndebele suffered a severe political defeat by the Boers, the Ndebele consciously returned to "the ancestor's ways", including making and using fertility dolls, in an attempt to re-establish and strengthen their culture identity.

Ndebele Fertility Dolls

When a couple is unable to conceive a child, their families carefully examine them. If no physical problems are readily apparent, the two then go to a diviner for treatment. Often the diviner discerns that the woman didn't go through initiation or it wasn't done properly. The wife is instructed to return to her father's home and undergo the rites again, this time carrying a fertility doll as surrogate child (E. Cameron 1996: 110). The multiple beaded bands around the fertility dolls are made from a straw rings covered with beads and worn around the neck, legs, arms, and waist. They imitate women who used to wear rings around their neck and legs. Both married and unmarried women may wear beaded body rings. Married women in addition wear metal neck, arm and leg rings (dzila) given to them by their husbands, offered public evidence of a man's wealth. The neck rings cannot be removed because they are associated with the ancestirs, the ancestors' wrath can be incurred if the rings are discared, possibly leading to illness or even death in the family (P. Magubane, AmaNdebele 2005: 32-34).

Ndebela aprons

Ndebele beadwork is a visual expression of communication system, which operates on a number of different levels. The manner and style in which these are worn, assumed a meaning and associated with ethnic identity- reveals the home area of the wearer, and reflects the social status of women - as the most common and distinctive types of beadwork are worn by women at various stages of their lives, as to communicate social identities in the community. The Ndebele are superb bead workers. They wear aprons which are heavily beaded with glass beads, clothing and ornaments as part of everyday dress

Dogon Art

The Dogon have a complex origin myth and cosmological system. The myth states that the first Dogon primordial ancestors, called Nommo, were bisexual water gods. They were created in heaven by the creator god Amma and descended from heaven to earth in an ark, and the encounter with the first inhabitant, the pale fox. The Nommo founded the eight Dogon lineages and introduced weaving, smithing, and agriculture to human descendants. The Dogon have three categories of ancestral spirits: 1. the mythic Nommo spirits founded their lineages form which the Dogon are descended. 2. Binu spirits, the ancestors in the form of animals, lived in mythic times before death was introduced to Dogon world. They became the protective totems of the clan, a source of power and protection. 3. Ancestors spirits from a person's real linage and clan ancestors, lived in this world. All types of these ancestor spirits are worshipped in shrines, ensuring their beneficial protectiveness to the community. Illness and infertility are the two main reasons for invoking magical assistance from the spiritual realm (Perani & Smith 1998: 48-50).

Ancestors Figures

Death is not the end of Life in Africa, the most ancient and basic belief is that Death is not natural and is the product of witchcraft (Soul Eaters). According to their belief, the Life force that Men and Beasts have (Nyama) can cause death as well.

The Africans believe that the dead live in another world but are also present with their relatives in this one. The same ancestors see and know all, so people must be careful with words and deeds, constantly aware that they are surrounded by the “Cloud of Witness”. According to this concept, the dead passing on to the World of the Dead are called the “Living- Dead” and are the most respectable part of the family. Their constant presence is felt daily: during feasts, portions are set aside for them, and at evening meals pots are not entirely emptied, nor washed till morning, in case the dead come and find nothing to eat. Particularly in the evening, they believed the ancestors are drawing nearer, and so after nightfall women will not sweep the house or throw water out into the yard, without first warning them out loudly.

During crises they are being presented with costly presents to enlist their help. In special ceremonies like initiations, feasts, crises and disasters, the Africans awaken their ancestors through the ancestors’ statues, to magically strengthen the community by promising protection, fertility, health, success and so on. The Ancestors’ Figures are meant to protect from hidden powers.

The is the reason why one of the most important duties of the African peoples, is to carry carefully the burial and later the mourning ceremonies for the dead, and often it followed with great expenses and accumulate debts – as a expression of filial feeling. For they believe that the angry ancestors will inflict upon them sickness and misfortunes - for neglecting in fulfilling the last rites with utmost care. Bad dreams are the reasons of anger of a restless spirit. Family life is strengthened by emphasis on performing full duties to the dead. Old men and women and parents are honored, and it is a great harm and humiliation to be cut off from the family. Without the protective benevolence of the ancestors, one is left without support, or protection – an easy victim of malevolence, never to be reincarnated again into a newborn child in the cycle of the family line -cut off from the flow of life continuity -the cycle of life (G. Parrinder, African Traditional Religion 1962).

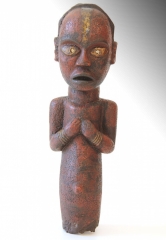

Mbete Art

The Mbete related to the Kota, living on the border of Gabon and the Republic of Congo. The use of containers holding relics of honorable ancestors is well known practice among the Fang, Kota and other tribes of the region, usually with a reliquary figure atop the receptacle guarding the sacred bones, but the Mbete created a new genre of figurative receptacle - wooden figures called mitsitsi-na-ngoye - with an interior cavity at its core covered with a small door. Clan leaders attributed mystical power to their venerated ancestor's relics, preserved within this hollowed interior, assisting in bringing success in hunting, defense, fertility and prosperity in the community's life (A.LaGamma 2007:266-7).

Asante Stool

The foundation of Asante's state was associated with one of its most important ritual objects, the Golden Stool (sika dwa kofi). According to the famous legend, in 1701 the Asante founder Osei Tutu was sitting under a tree, when out from the thunder and lightning-filled heaven a golden stool floated down to his lap. It was interpreted by his diviner as representing the soul or the spirt of Asante's nation, and became a symbol of the kingdom's unity and vitality. So sacred was the stool that it could never be touch the ground, placed on a European-style chair and elephant mat. Only the king can sit on it in the course of installation and state ceremonies. The death of a leader was spoken of by saying "a stool has fallen". The ancestral spirit of the Akan peoples was believed to reside not in figurative image, but in a specific stool, which ritually blackened with sacrificial offering. Ancestor cults for royal and non-royal Akan were focused on "stool rooms" where these symbols were housed (Cole 1989:79)

Two As One - Images of Male & Female Attached

Images of male – female couples have a great range of identifications: married couples, other world lovers (baule), mythical progenitors (dogon), twins (ibeji), ancestors and a host of other gods and spirits. Behind such labels lie rich constellations of meaning that account for the existence of sculptured and dance representation of couples in Africa. This help people understand themselves, the world, and the paradox: two are one. (Cole1989:52-3). For young initiates, these statues explained the necessity of dualism existing in nature, the social differentiation between men and women, and the distinction between the sexes – dualism one had to transgress in order to attain perfection, continuity and fertility in life (Leloup 1994).

Masks

The masks or figures were not symbols of abstraction, they were for the animistic Africans: containers, or retainers of spirit power, dwelling places for the invisible forces of the ancestors's souls. It was not the carving which was the subject to worship, but the forces which it contained. Animism was for the Africans the foundation for most of their religio-magical rituals. Masks were "spirit traps" as the African called them, aiming at all time to control the function of ancestors' spirits for the benefit of the living. They were based on the concept that through the appropriate rituals man could conjure up the vital forces (nyama) dwelling in the masks or figures by gaining the benediction of his ancestor in order to promote fertility, protection and success.

Each mask had multiple meanings, and acquired a specific significance in each separate ritual based upon the established oral tradition. The participants in the ritual knew its conceptual basis from historic, mythic, or social data learned from childhood and emphasized in the initiatory teaching. Within this multiplicity of uses and meanings, one is recurring often – the use of the same mask in fertility, agricultural and burial ceremonies. All the three ceremonies using the same mask had one common aim: fertility. Fertility of the earth - for the sacredness of the soil, which belonged to the ancestors, or the "masters of the soil", thus, the successful harvest depended on the benediction of these ancestors. Procreation - the fusion of male and female producing offspring, this includes human and animal fertility, symbolically the fertility of the earth. Third, since in the African's mind the fertility of the earth and human was connected with ancestor's spirits, he maintained contact with these spirits at burials and rituals of ancestor worship. The ancestor was often associated with human fertility. They believed as have said, in incarnation – when a child was about to be born, they consulted their diviner to find out which ancestor would return in the body of the baby, and accordingly, the infant received the ancestor's name. Thus, the cycle of life continues in traditional African life (L. Segy Masks of Black Africa 1976:20-21, 26-28).