The Ancestor Cult

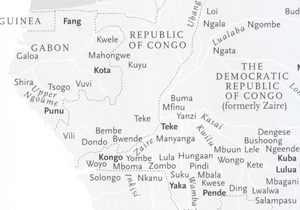

This exhibition presents over 70 artifacts from 14 distinct societies living in five different African nations: Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, The Republic of Congo, and The Democratic Republic of the Congo (Zaire).

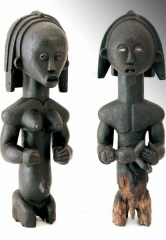

The majority of peoples represented in this exhibition include the various Fang groups:Betsi, Mabea, Mvai, Ngumba, Ntumu, and Okak. In addition, the neighboring tribes: Kota and related Mahongwe, Shamaye and Sango, also Punu, Kwele, Tsogho Mbete (Ambete) and Teke.

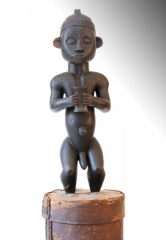

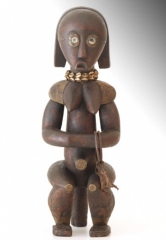

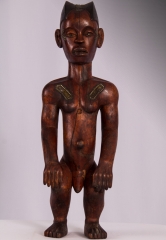

Though each tribe retains its artistic style, the Ancestor cult is the main motive for them all. The tribes jealously guarded the relics of important ancestors – skulls or small bones of the most venerated ancestors, considering them to contain the supernatural powers that allowed for their success while alive. These skulls were placed in a bark container and were maintained at the house of each lineage head. The carved-wood figures, which has been gathered on this exhibition - were inserted into these bark containers (reliquary box), and were called eyema-o-byeri, by the Fang. They were conceived as “protective” or “guardian” figures, to cast away harmful spirits. The reliquary guardianship was intended against the intrusion of unseen enemies. Witchcraft is one of the basic elements of the traditional religion. Each powerful person is assumed to be associated with supernatural beings who gave him the power to do well or harm in unseen ways. The struggle for personal power, prestige and reputation in the region is great; it is believed to be the most intense - in the unseen world. So rivals supposed to focus their occult powers on each other’s reliquaries, and thus the guardian reliquary was intended to ward off supernatural interference with the power of their relics in the reliquary basket. In times of special occasions, such as initiation rite, festivals or time of misfortune, death or sickness, the ancestor reliquaries were invoked, expected to strengthen the community magically, to assure their benevolence protection for the community well-being, fertility, success in hunting, trading and so on.

Ancestor cult in the course of years has been a convenient generalization for much of the religious or ritual activity practiced in Africa. In Africa, God rarely intervenes in everyday life of men on earth. It is the ancestors who act as the official guardians of the social and moral order. In such societies, the ancestors become the focus of religious activity. Belief in the continued existence and influence of the departed fathers of the family and tribe is very strong in all Africa. Not only are the ancestors revered as past heroes, but they are felt to be still present. They are called “the living-dead”- watching over the household, directly concerned in all the affairs of the family and property, giving abundant harvests and fertility. But they punish with sickness or misfortune, those who infringe them. Old men and women and parents are honored, and it is a great harm and disgrace to be cut off from family and the flow of life continuity. Without the protective benevolence of the ancestors, one is left without support, or protection – an easy victim of witchcraft and malevolence.

Ancestor cult in the course of years has been a convenient generalization for much of the religious or ritual activity practiced in Africa. In Africa, God rarely intervenes in everyday life of men on earth. It is the ancestors who act as the official guardians of the social and moral order. In such societies, the ancestors become the focus of religious activity. Belief in the continued existence and influence of the departed fathers of the family and tribe is very strong in all Africa. Not only are the ancestors revered as past heroes, but they are felt to be still present. They are called “the living-dead”- watching over the household, directly concerned in all the affairs of the family and property, giving abundant harvests and fertility. But they punish with sickness or misfortune, those who infringe them. Old men and women and parents are honored, and it is a great harm and disgrace to be cut off from family and the flow of life continuity. Without the protective benevolence of the ancestors, one is left without support, or protection – an easy victim of witchcraft and malevolence.

Ancestor worship is well known in Western art, especially in Christian art of the middle Ages, although we don’t usually think of the ancestor cult as occupying an important place in art history. The veneration of ancestors was practiced in Classical Greece and Rome. In the Republican Period of Rome, wax imagines, or portrait masks of dead family members were preserved in the atrium of patrician homes, where they received offerings and were honored in much the same way as is still practiced in traditional African societies today, and particularly in the pre-colonial era. Masks in an idealized form were used by the Greeks; painted wax masks were collected by patrician families in Rome, where actors were wearing them as part of the funerary ceremony, (a costume of Etruscan origin), as seen in an Roman statue of a patrician carrying busts of his ancestors in a funeral procession. Or to quote Pliny: "In the halls of our ancestors, wax models of faces were displayed to furnish likenesses in funeral processions, so that at funeral the entire clan was present" (Pliny, N.H., xxxv .2). Again, in the same custom as is practiced in traditional African societies today. But while Roman artists were using an idealized form, though they also tried to be close to naturalistic portraits, Africans creates a portrait that represents the ancestors, yet they are far from naturalism. All the tribes presented in the exhibition regards the ancestors as an important and central issue in the religion, culture and every day life.

Ancestor worship is well known in Western art, especially in Christian art of the middle Ages, although we don’t usually think of the ancestor cult as occupying an important place in art history. The veneration of ancestors was practiced in Classical Greece and Rome. In the Republican Period of Rome, wax imagines, or portrait masks of dead family members were preserved in the atrium of patrician homes, where they received offerings and were honored in much the same way as is still practiced in traditional African societies today, and particularly in the pre-colonial era. Masks in an idealized form were used by the Greeks; painted wax masks were collected by patrician families in Rome, where actors were wearing them as part of the funerary ceremony, (a costume of Etruscan origin), as seen in an Roman statue of a patrician carrying busts of his ancestors in a funeral procession. Or to quote Pliny: "In the halls of our ancestors, wax models of faces were displayed to furnish likenesses in funeral processions, so that at funeral the entire clan was present" (Pliny, N.H., xxxv .2). Again, in the same custom as is practiced in traditional African societies today. But while Roman artists were using an idealized form, though they also tried to be close to naturalistic portraits, Africans creates a portrait that represents the ancestors, yet they are far from naturalism. All the tribes presented in the exhibition regards the ancestors as an important and central issue in the religion, culture and every day life.

Sources:

James Fernandez, Bwiti: an ethnography of religious imagination in Africa, 1982, pp. 253-270; Geoffrey Parrinder, Ancestor cult ,African Traditional Religion, 1962,Sheldon Press, London; Benjamin C. Ray, African Religion, Symbol, ritual, and community, 1975, pp. 146-152; Elizabeth Broudy, Ancestor Cult, 1975, Cranbrook Academy of Art, Michigan, pp. 64-5; L. Perrois, Fang, 2006; Donald Strong, Roman Art, 1976,p,25; Michael Avi Yona, History of Classic Art, pp 216, 224; Mortimer Wheeler, Roman Art and Architecture, 1976, pp.162-3,fig.142; Pliny op. cit. ibid, p. 162; Alisa Lagamma, Eternal Ancestors, 2007,fig.58.